Got Buffers?

- Spencer Easton

- Nov 30, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 21, 2022

The vast majority of professionals in construction are conditioned to add "fluff" to a schedule so they have enough time for their projects. This causes unintended and negative results including:

Unreliable Schedules - Because the dates for future activities are not correct or reliable, project teams cannot rely on them. This is what we call, "moving target syndrome" and the real reason why CPM, Bar charts, and gantt charts are abandoned or don't reflect what is happening in the field.

Two Schedules - Because industry teams are trying to hide the fluff in a schedule, they typically keep two schedules-a schedule to drive the actual durations of production, and the other to communicate to the owner.

Hidden or Lost Data - When "fluff" is added in the schedule and not notated or visible it can be lost, making it harder to improve or optimize the plan.

Fake: SS, FF, Lags - When "fluff" can't be added to activity duration because of some requirement, most professionals resort to adjusting logic or relationship ties that are hidden and harder to verify what they mean. This is why there are scheduling specifications out there that require a rational for each lag and safeguard each relationship link with special software and reports, but this is over-processing.

Lack of Trust - Owners have seen this and is the big reason why there are third party schedule auditors, large CPM specifications, and a negative stigma against time buffers in construction schedules.

Yet there is a very high likelihood that something will happen on our job sites that prevents us from producing work 100% on time according to a "critical path."

This is called inevitable variation, we live in the real world and just like Mike Tyson said, "Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth".

This is where we find ourselves, looking for a way to minimize the negatives in the list above. But knowing deep down that we still needing to adjust our schedules for life's variation thrown at us. So the best of both worlds is planning to get punched in the mouth and having a process on how to deal with it.

A study done by Greg Howell, Marion Russell, Simon Hsiang, and Min Liu identified 47 potential inevitable types of variation that builders may encounter during the life cycle of a project. They examined data from 36 different construction companies across the United States and found these categories were the major rational on why buffers need to be in any construction plan & schedule. Here is a shortened list:

Unique Project Characteristics

Prerequisite Work Not Complete

Detailed Design / Working Method Not Finalized

Labor Force Inefficiency

Equipment and Tools Not Adequate

Materials and Components Not Available

Work / Jobsite Conditions

Management/Supervision/Information Flow Interruption

Weather

you can dive deeper into their findings in their paper published with the IGLC:

Their study shows us that there are many types of fluctuations that we will face in construction and that we will need a few different ways to account for the different types of variation we will face.

In another study about construction buffers by Janosch Dlouhy, Marco Binninger and Shervin Haghsheno we are shown why Takt is the best system for finding available buffer time in our schedules. This gives us a systematic way to account for and visualize these buffers and use them to absorb variation.

Work-packaging & Parallelization

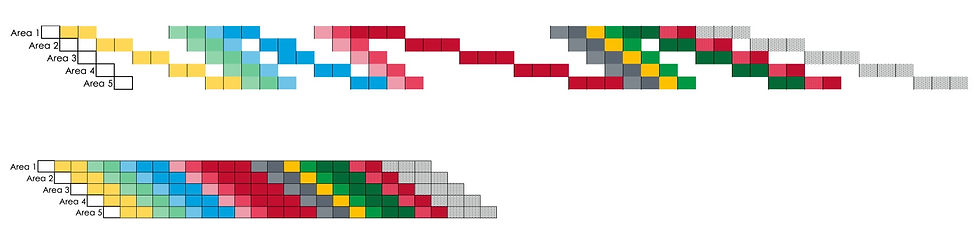

The first step to gaining buffers in a schedule is to focus on work-packaging and parallelization. This means we package work steps into work packages that become Takt wagons.

When things are "paralleled or packaged" together it obviously allows for more time in our schedule. (See image above)

The process is quite simple. We first understand the sequence of work with the teams input, and we review the time frame identified for each task. The Takt time will become apparent as the packaging process takes place. Work activities will be gathered into Takt wagons which creates our Takt sequence and legend.

Once the work packages (scopes of individual process types) are in a wagon, we then can create the unoptimized takt plan. Just following this step will allow more time than traditional planning. To see this detailed process see this video:

From there you can start to adjust your batch size to find more time to allow us time for buffers. The video above should have explained this well for you.

Batch/lot Size Reduction

Using Little's Law (a production law) applied for construction, we can find extra time that allows us to add in the buffer at net zero duration change to the original plan. Meaning that if you are on a job right now and are dealing with a tight time frame and falling behind, the best recovery tool that will give you the best chance to finish on or ahead of time is Takt. Click on colored image above for video on Little's Law Calculation.

Below is another great visual on ensuring we have the right batch sizes and are properly using parallelization.

In the image above there are three schedules that have 4 scopes of work to complete. Changing from schedule 1 to 2 is breaking up the work into three sub areas or three small takt zones. If this is completed you can then achieve schedule 3 which is aligning them and finishing as you go. Allowing you 6 time frames from 7-12 that is now able to be used as buffer time to adjust for variation.

Harmonization

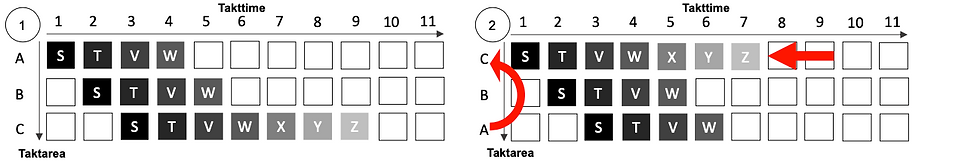

Looking at the image above you can see there are different durations for each activity, and this example also shows that there are some activities are not in some areas. On the Left we see a standard CPM waterfall type representation of a schedule; while on the Right we see the harmonization of the same information with the same overall duration of time per scope of work.

This is not only doing what some might call line of balancing but it is also allowing for the differences in your production areas and still accounting for the empty takts which should not be considered buffers. If the design changes and all scopes end up being in all areas these "empty takts" would be filled with this work.

Thus, just by harmonizing the sequence and production you will find a large % of time hidden in your schedule.

Logistical Sequencing / Long Running Processes

If you have a list of takt zones that all have the same sequence but one of them has a large amount of work or more work-packages you will be able to sequence the zones in a way that you find lost and hidden time. Prioritizing the longest train first in the logistical sequence will reduce your overall duration. This is a simple one to map out, test it both ways and see what your results are. Just like above the extra time is sitting there just because the overlap of subsequent work.

If you want to read the whole paper by Janosch Dlouhy, Marco Binninger and Shervin Haghsheno here is the link to their IGLC Paper:

So how and where are we supposed to add buffers? Here is the answer that we will simplify for you.

We have made a really nice one sheet that will help you as a guide when adding buffers you can download it here for free:

The major buffer types with some examples are:

Systemic buffer: This is a buffer type that is naturally a part of the system. An example of this would be Saturday and Sunday at the end of a 5-day Takt time.

Empty Takt: This is simply a Takt or cell in Excel that is left empty and serves as a buffer.

Takt time buffer: An entire Takt time scale is used as a buffer in the system. Carving out the weeks of Thanksgiving and Christmas as a buffer in the United States is an example of this.

Buffer wagon: This is a wagon that serves as a buffer within the Takt sequence.

Wagon buffer time: This is a small buffer built into the actual Takt wagon itself. This means the wagon within the Takt time is not planned to be 100% efficient.

Calculated end buffer: The CEB is the buffer shown at the end of the project that can be considered the project buffer or contingency in the schedule.

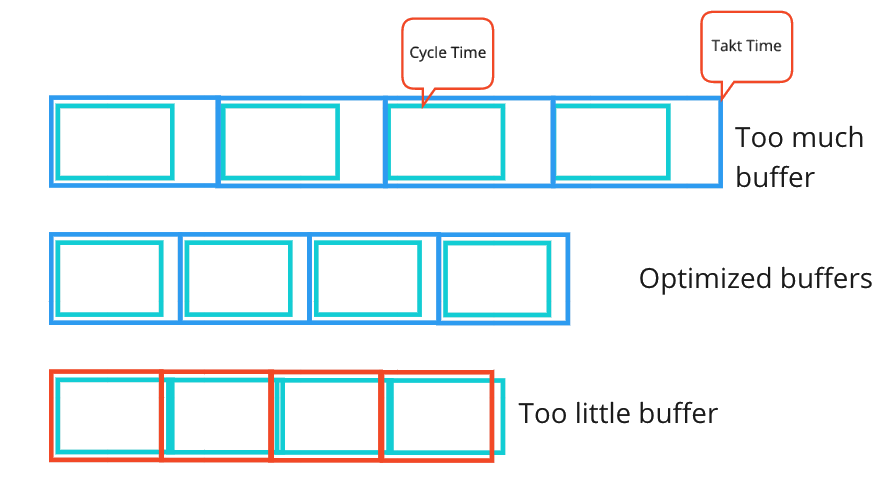

There are buffers at the Takt Time level, Work-package level, the Macro Level, The Takt system level, a cycle time level and just about everywhere we look .... But we can't just add in buffers everywhere because it would cause waste.

The image below is a simplified way of communicating that there is a point at which there will be too much buffer and that is just as bad as too little.

This turns into a balancing act where we review, watch and monitor each Takt time within the Takt production system and during Takt control. If you have too many buffers you adjust. If you have too little you adjust. And you get it to the optimized spot where the work can proceed clean and steady.

There is one last help we will provide. There is something called the Stability Parametric that shows us when we are balanced with our buffers in our takt plan. Here is a quick image that will help you see how this works:

This is why there is no Takt plan without buffers and why I titled this post Got Buffers? Because if you don't.... you are not Takt planning.

If you want to learn more we have:

Takt Training " Takt Fundamentals"

A great podcast called "The Elevate Construction Podcast with Jason Schroeder"

The leanTakt YouTube Channel dedicated to showcasing how to do takt and sharing.

The leanTakt Website with tons more resources and content www.leanTakt.com

The Takt Book "Takt Planning and Integrated Control" by Jason and Spencer

Builder, Foreman, and Field Engineer Bootcamps " Upcoming Events"

Further light and knowledge from our Expert counterparts in Germany Takt.ing

If you need help with anything you can always reach out to Jason Schroeder.

On we go!

Komentar